Starring: Jo Shishido, Koji Nanbara, Mariko Ogawa, Annu Mari

Director: Seijun Suzuki

Rating: 10/10

Seijun Suzuki was already the veteran of 38 features when he made Branded to Kill (1967), but it betrays no signs of flagging inspiration; instead, the director shaped the material with stunning audacity, turning what was supposed to be just another yakuza quickie into an absurdist commentary on Japanese corporate culture and tough guy codes. Apparently, the studio bosses were so horrified with the result that Suzuki was banished to work in television for the next ten years, and it didn’t do much for leading man Jo Shishido’s career either. But anyone watching this Blu-ray will probably take both men to their hearts as cinematic heroes, because Branded to Kill is a wondrous, transporting, intense, witty, irreverent viewing experience of a kind that comes along all too rarely.

Seijun Suzuki was already the veteran of 38 features when he made Branded to Kill (1967), but it betrays no signs of flagging inspiration; instead, the director shaped the material with stunning audacity, turning what was supposed to be just another yakuza quickie into an absurdist commentary on Japanese corporate culture and tough guy codes. Apparently, the studio bosses were so horrified with the result that Suzuki was banished to work in television for the next ten years, and it didn’t do much for leading man Jo Shishido’s career either. But anyone watching this Blu-ray will probably take both men to their hearts as cinematic heroes, because Branded to Kill is a wondrous, transporting, intense, witty, irreverent viewing experience of a kind that comes along all too rarely.

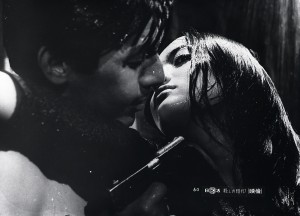

Shishido plays Hanada, a smart, ruthless killer, No. 3 in the organization. We see just  how sharp and resourceful he is early on when he has to collect a VIP from the airport and transport him through a gauntlet of gunmen waiting in ambush. But this outwardly cool and collected professional also has quirky inner life, as we learn from one of the first big surprises of the movie, a stylish and funny montage sequence which shows Hanada and his wife (Mariko Ogawa) at home, chasing each other around their Vegas-style apartment and making love in the bath, in the hallway and on the flimsy-looking spiral staircase. In addition, Hanada has a comical fetish for the smell of freshly cooked rice; a whiff of it has him rolling his eyes in excitement. You never saw Alain Delon or Lee Marvin acting that way.

how sharp and resourceful he is early on when he has to collect a VIP from the airport and transport him through a gauntlet of gunmen waiting in ambush. But this outwardly cool and collected professional also has quirky inner life, as we learn from one of the first big surprises of the movie, a stylish and funny montage sequence which shows Hanada and his wife (Mariko Ogawa) at home, chasing each other around their Vegas-style apartment and making love in the bath, in the hallway and on the flimsy-looking spiral staircase. In addition, Hanada has a comical fetish for the smell of freshly cooked rice; a whiff of it has him rolling his eyes in excitement. You never saw Alain Delon or Lee Marvin acting that way.

But then they didn’t have to put up with the pressure of being No. 3 killer. It’s all very fine, but one slip and he could lose his ranking and his life (the organization is like existence itself; there’s no way out except feet first). His worst fears are realized when a mysterious girl, Misako (Annu Mari) hires him for a job and it goes wrong for a whimsical reason entirely beyond his control. Suddenly, the hunter is the hunted and he has none other than the No. 1 killer after him.

But then they didn’t have to put up with the pressure of being No. 3 killer. It’s all very fine, but one slip and he could lose his ranking and his life (the organization is like existence itself; there’s no way out except feet first). His worst fears are realized when a mysterious girl, Misako (Annu Mari) hires him for a job and it goes wrong for a whimsical reason entirely beyond his control. Suddenly, the hunter is the hunted and he has none other than the No. 1 killer after him.

From there, the film spirals, or unhinges, into more and more hallucinatory and  outlandish set-pieces that see Hanada leaving his hip, rat pack cool far behind and becoming a raving figure of paranoia. It’s all presented in Suzuki’s eclectic yet assured visual style, one that combines jittery Godardian jump-cuts and alienating camera angles with sleek, high contrast, widescreen black-and-white cinematography that seems to hark back to ’50s Hollywood films such as Sweet Smell of Success. It’s a style that somehow balances swagger and cool detachment. The early fight scenes are lensed mostly in extreme long shot, making the figures look tiny, their disputes insignificant. Suzuki is more interested in the trappings of the gangster world than the violence: those same sequences often frame Hanada against his (very nice) car, gun raised; it’s like he’s clinging to it not just for protection but for the sense of status it conveys.

outlandish set-pieces that see Hanada leaving his hip, rat pack cool far behind and becoming a raving figure of paranoia. It’s all presented in Suzuki’s eclectic yet assured visual style, one that combines jittery Godardian jump-cuts and alienating camera angles with sleek, high contrast, widescreen black-and-white cinematography that seems to hark back to ’50s Hollywood films such as Sweet Smell of Success. It’s a style that somehow balances swagger and cool detachment. The early fight scenes are lensed mostly in extreme long shot, making the figures look tiny, their disputes insignificant. Suzuki is more interested in the trappings of the gangster world than the violence: those same sequences often frame Hanada against his (very nice) car, gun raised; it’s like he’s clinging to it not just for protection but for the sense of status it conveys.

Yet Suziki also has an equally unerring eye for the shock factor, the impactful moment: there’s an extraordinary stunt of a baddie running along hell for leather, his thin Italian suit wreathed in flames. And the movie culminates in a shootout and a half, with Hanada taking on multiple opponents on a narrow bridge – a sequence as agonized and sun-baked and operatically drawn out as anything you’ll see in a spaghetti western.

Yet Suziki also has an equally unerring eye for the shock factor, the impactful moment: there’s an extraordinary stunt of a baddie running along hell for leather, his thin Italian suit wreathed in flames. And the movie culminates in a shootout and a half, with Hanada taking on multiple opponents on a narrow bridge – a sequence as agonized and sun-baked and operatically drawn out as anything you’ll see in a spaghetti western.

And there’s more. Even as Suzuki twists the yakuza genre inside out and plays it for  mordant laughs, he brings a whiff of something else – the supernatural. Although it’s never explicitly stated, Misako, the girl who hires him, has undertones of being a creature of ill omen, a vengeful ghost or evil spirit. She’s surrounded by morbid and threatening imagery. Her sports car has a dead mynah bird dangling from the rearview mirror where most people would have a pair of furry dice; she lives in an apartment full of displays of dead butterflies that seem to multiply and grow impenetrably thick. As the storyline becomes more erratic, less susceptible to logic, it crosses your mind to wonder whether Hanada might not have died at some point without you noticing – maybe this is all some kind of yakuza purgatory?

mordant laughs, he brings a whiff of something else – the supernatural. Although it’s never explicitly stated, Misako, the girl who hires him, has undertones of being a creature of ill omen, a vengeful ghost or evil spirit. She’s surrounded by morbid and threatening imagery. Her sports car has a dead mynah bird dangling from the rearview mirror where most people would have a pair of furry dice; she lives in an apartment full of displays of dead butterflies that seem to multiply and grow impenetrably thick. As the storyline becomes more erratic, less susceptible to logic, it crosses your mind to wonder whether Hanada might not have died at some point without you noticing – maybe this is all some kind of yakuza purgatory?

Some critics have suggested much the same thing of Lee Marvin’s character in Point Blank, and it’s one of many points of resemblance between Suzuki’s film and John Boorman’s. Both films are dazzlingly stylish, pungently nihilistic neo gangster movies – but Suzuki is far more daring and outrageous. Branded to Kill even has an enticing female character to match Angie Dickinson, in the impish form of Mariko Ogawa. As Hanada’s wife, Mami, she goes strutting around their flat in her birthday suit, asserting a teasing, high-spirited sexuality which is important for the film because it helps to make Hanada seem more human and likeable (it seems to have been the only movie she ever made, sadly – she was brought in from outside the Nikkatsu studio because none of their contract actresses would agree to do nude scenes – but it’s a delicious performance). If you like Point Blank, it’s almost guaranteed that you’ll fall head over heels in love with this film too. It really is that good.

Some critics have suggested much the same thing of Lee Marvin’s character in Point Blank, and it’s one of many points of resemblance between Suzuki’s film and John Boorman’s. Both films are dazzlingly stylish, pungently nihilistic neo gangster movies – but Suzuki is far more daring and outrageous. Branded to Kill even has an enticing female character to match Angie Dickinson, in the impish form of Mariko Ogawa. As Hanada’s wife, Mami, she goes strutting around their flat in her birthday suit, asserting a teasing, high-spirited sexuality which is important for the film because it helps to make Hanada seem more human and likeable (it seems to have been the only movie she ever made, sadly – she was brought in from outside the Nikkatsu studio because none of their contract actresses would agree to do nude scenes – but it’s a delicious performance). If you like Point Blank, it’s almost guaranteed that you’ll fall head over heels in love with this film too. It really is that good.

The HD transfer is sleek and near-immaculate, with just a touch of very fine grain  here and there, and the beautiful deep focus compositions, the night-time sequences of neon and cocktails bars, the stylized, otherworldly scenes in Misako’s apartment, all are as vivid as your own dreams. Extras include a 7-minute interview with Suzuki, recorded in 2001. He explains that because nudity wasn’t allowed under the Japanese motion picture code at the time, the film was released with moving arrows that followed Mariko Ogawa around, covering the troublesome areas – which must have been terribly distracting, so perhaps it’s not surprising that audiences failed to notice that they were watching a masterpiece (no arrows are present on this Arrow release, thank heavens). There’s also a 17-minute interview with Shishido, who talks about the fire stunt and again about the nude scenes (Degas paintings were used as a reference), and has more to say about his character’s fetish for freshly cooked rice – it’s not just that he likes it, the smell is supposed to give him an instant erection.

here and there, and the beautiful deep focus compositions, the night-time sequences of neon and cocktails bars, the stylized, otherworldly scenes in Misako’s apartment, all are as vivid as your own dreams. Extras include a 7-minute interview with Suzuki, recorded in 2001. He explains that because nudity wasn’t allowed under the Japanese motion picture code at the time, the film was released with moving arrows that followed Mariko Ogawa around, covering the troublesome areas – which must have been terribly distracting, so perhaps it’s not surprising that audiences failed to notice that they were watching a masterpiece (no arrows are present on this Arrow release, thank heavens). There’s also a 17-minute interview with Shishido, who talks about the fire stunt and again about the nude scenes (Degas paintings were used as a reference), and has more to say about his character’s fetish for freshly cooked rice – it’s not just that he likes it, the smell is supposed to give him an instant erection.

And then…

As an amazing bonus, we get Trapped in Lust (1973), a yakuza film by Atsushi Yamatoya, who was one of the screenwriters on Branded to Kill (this was the last of three features he directed). It recycles a few of the same plot points but very much has its own point of view. Genjiro Arata plays Hoshi, a surly, unthinking brute of a hitman who is so tough he makes love to his wife with his sunglasses on. But when she and his mentor in the organization double-cross him, he finds himself being targeted by the organization’s top enforcer, a totally creepy villain who confuses and terrorizes his victims by dressing up as a ventriloquist and dummy (a girl with a straw boater – yes, it just keeps on getting creepier). Never one to back down from a fight, Hoshi goes on a bloody revenge spree.

The vibe is very much of the ’70s – Trapped in Lust is shot in brownish, autumnal colour, with a cast of jaded, seedy characters who look like they’ve slept in the clothes they’re standing up in. Packing a huge amount into its 73 minutes, it delivers on a basic level as a raw, gritty yakuza flick with plenty of sex and violence, but there’s more to it than that: hardboiled as it is, it also feels deconstructed and wearily knowing about its own mechanics, and it takes an almost valedictory attitude to the yakuza genre: in his crumpled suit, Hoshi is a literally threadbare character, and the final shootout takes place in an empty cinema, as though to suggest that the audience has moved onto other spectacles. If Branded to Kill seems to pair nicely with Point Blank, Trapped in Lust conjures up a similar terminal atmosphere to end of the line ’70s gangster flicks such as Prime Cut and The Friends of Eddie Coyle.

It undoubtedly has its flaws. Its psychology is crude – a rather crass and obvious linkage is made between Hoshi’s skills as button man and his sexual prowess, and when he can’t perform one to his satisfaction, the other lets him down too. The routine sexual violence towards women might make some viewers baulk, particularly a scene – shocking, bizarre, and once seen, never forgotten – where Hoshi’s wife Mayuko (played by a prolific porn actress Moeko Ezawaso – this was one of thirteen films she appeared in that year) is violated by that weird ventriloquist’s dummy. Then again, it’s at least arguable that the rape justifies itself in terms of its dramatic impact in the story – after that, anything seems possible, the nihilism and breakdown of order feel complete and overwhelming.

In its own way, Trapped in Lust is almost as striking as Branded to Kill, although not nearly so endearing. The HD transfer is a just little soft but very clean and without grain, and those typical ’70s colours – brown, saffron, mustard, orange, pepper and salt – come across with natural fidelity. With these two exciting and rarely scene films brought together on a single Blu-ray, this release is an unmissable bargain for anyone remotely interested, not just in Japanese cinema, but in the films of the ’60s and ’70s. Suddenly the picture of that period seems incomplete without an appreciation of Seijun Suzuki and his followers.

In its own way, Trapped in Lust is almost as striking as Branded to Kill, although not nearly so endearing. The HD transfer is a just little soft but very clean and without grain, and those typical ’70s colours – brown, saffron, mustard, orange, pepper and salt – come across with natural fidelity. With these two exciting and rarely scene films brought together on a single Blu-ray, this release is an unmissable bargain for anyone remotely interested, not just in Japanese cinema, but in the films of the ’60s and ’70s. Suddenly the picture of that period seems incomplete without an appreciation of Seijun Suzuki and his followers.